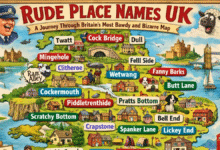

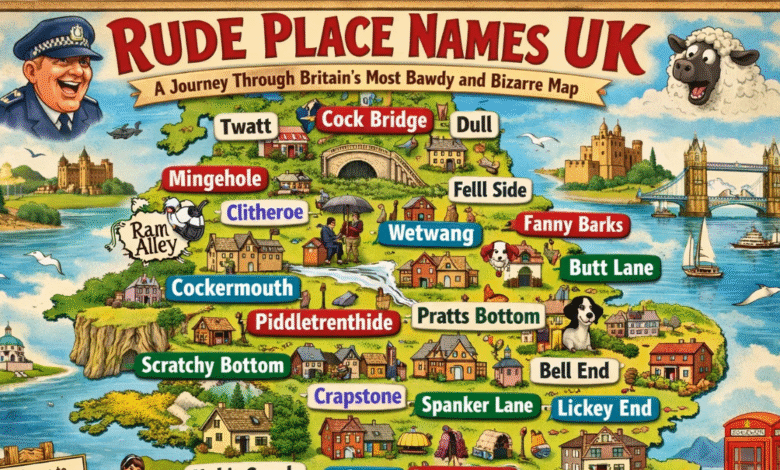

Rude Place Names UK: A Journey Through Britain’s Most Bawdy and Bizarre Map

Rude Place Names UK Imagine planning a road trip across the British countryside, only to find your satnav directing you through a landscape that sounds like it was named by a medieval stand-up comedian with a penchant for bodily functions. Welcome to the uniquely British phenomenon of rude place names UK. From villages that provoke a snigger to hamlets that cause outright disbelief,

the map of the United Kingdom is dotted with locations whose monikers seem hilariously, bafflingly inappropriate to the modern ear. This isn’t a mere quirk of history; it’s a linguistic archaeology project, uncovering layers of social history, evolving language, and an enduring, robust British sense of humour that refuses to be sanitised.

This comprehensive guide will serve as your definitive atlas to these extraordinary places. We’ll move beyond the simple listicle to delve into the profound historical, linguistic, and cultural reasons why these names emerged, why they survived centuries of societal change, and what they tell us about our ancestors and ourselves. We’ll explore everything from Old English slang to Victorian prudery, from passionate local campaigns to protect these names to the simple, timeless truth that sometimes, a place name is just what it sounds like. So, fasten your seatbelts for a journey to rude place names UK enthusiasts cherish, where history is anything but polite.

The Linguistic Roots of Ribaldry

To understand why so many rude place names UK exist, we must first divorce ourselves from modern interpretations. The vast majority of these names are not deliberate vulgarities but are instead innocent products of ancient languages, primarily Old English and Old Norse, whose words have shape-shifted over a millennium into something provocative. The Old English word “scīte,” for example, simply meant “dung” or “landing place,” a practical descriptor for manured farmland. Over centuries, “scīte” evolved into the modern vulgarism, transforming functional places like Shitterton in Dorset (originally “Scitereton” – the farm on the brook where dung was deposited) into a source of endless amusement.

Similarly, the prefix or suffix “-cock” is almost always derived from the Old English “-cocc,” meaning a “hillock” or “small heap.” Hence, places like Cockup Hill in Cumbria refer not to an error but to a small, rounded hill. The evolution of language is the greatest trickster here; words that were once blandly topographical have been hijacked by subsequent slang, casting a cheeky shadow back through time. Recognising this linguistic journey is crucial—it reframes these rude place names UK collections celebrate from juvenile jokes to fascinating fossils of speech.

A Typology of Teasing: Classifying the Name Game

Not all impolite place names are created equal. They fall into distinct categories based on their origin and impact, which helps us analyse them more systematically. The first and largest category is the Innocent Etymology group, where archaic terms have morphed into modern rudeness, as with the “scīte” and “-cocc” examples. The second is the Literally Descriptive category, where our ancestors called a spade a spade with breathtaking bluntness, leading to names like Muck in County Durham or Brown Willy (a Cornish hill, from “bronn” for hill and “ewhel” for eagle).

The third category is the Playfully Punning or Coincidental, where names accidentally combine to create humorous phrases, like Westward Ho! in Devon (the only UK town with an exclamation mark, named after a novel) or the delightful proximity of Upper Dicker and Lower Dicker in Sussex. Finally, there’s the rare category of Apparent But Unproven—names where the rude connection is tempting but the historical evidence is shaky. Understanding this typology allows us to appreciate the nuance behind each rude place names UK explorers seek out, separating linguistic fact from playful fiction.

| Category | Description | Primary Origin | Example | Modern Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innocent Etymology | Old words that have become slang. | Linguistic evolution. | Crapstone, Devon (from “craep,” meaning a rocky outcrop). | Obscene exclamation. |

| Literally Descriptive | Blunt, factual naming based on local features. | Pragmatic observation. | Muck, County Durham (likely from “muc,” meaning pig). | General dirt or mess. |

| Playfully Punning | Accidental or deliberate humorous combinations. | Coincidence or later wordplay. | Bell End, Worcestershire (a street at the end of a bell-shaped land plot). | Crude slang. |

| Apparent But Unproven | Names where rude links are popular but historically unconfirmed. | Folk etymology. | Gropecunt Lane, (medieval, various cities) – well-documented but now lost. | Explicit term. |

Historical Context: A Less Refined World

Our medieval and early modern ancestors lived in a world far more directly connected to the realities of the body, agriculture, and the land than we are today. Sanitation was rudimentary, life was physically demanding, and language reflected that raw, unfiltered existence. In this context, naming a stream “Shitbrook” (a common medieval name for a sewer or dung-carrier) was no more offensive than naming a hill “Sunnybank”—it was simply a useful identifier. The famous Gropecunt Lanes found in many medieval cities (like London and York) were unambiguous: they were districts where sex workers plied their trade.

This straightforwardness extended beyond the scatological. Names like Slutshole Lane in Norfolk or Pissing Alley in London spoke of a society that had not yet undergone the linguistic cleansing of the Victorian era. These rude place names UK historians study were not created to shock; they were created to communicate efficiently within a community that saw little need for euphemism when describing the functional aspects of daily life. They are snapshots of a pre-industrial mindset, where the map was a practical document, not a polite one.

The Victorian Purge: A Campaign for Clean Maps

The 19th century brought a wave of moral rectitude and linguistic prudery that viewed Britain’s bawdier toponyms with profound distaste. The Victorian drive for “improvement” and decency extended to the landscape itself, leading to the most systematic campaign of name-changing in British history. Across the country, local authorities and embarrassed citizens petitioned for changes. Pissing Alley became Passing Alley, Gropecunt Lane was invariably renamed Grape Lane (a tidy bowdlerisation), and Slutshole Lane was discreetly altered.

This period of sanitisation explains why so many of the most explicitly rude place names UK might have had are now lost to history, surviving only in dusty archives or court records. The Victorians preferred names that evoked romance, royalty, or industry over earthy honesty. However, their campaign was not entirely successful. In many rural, stubborn communities, the old names persisted in local speech long after they were officially scrubbed from the map, a quiet act of defiance against imposed gentility.

Modern Resilience: The Fight to Keep a Straight Face

In stark contrast to the Victorian puritans, the modern era has seen a passionate movement to preserve these hilariously awkward names. Residents often display a fierce, proud local identity tied to their uniquely-titled home. The village of Shitterton in Dorset famously spent thousands of pounds in the 1980s to haul a several-tonne block of Purbeck stone into the village and carve “Shitterton” into it, ensuring the name could not be easily removed or altered by the council. This is more than just a love of a joke; it’s about heritage.

As the historian Dr. Adam Fox notes, “Place names are the deepest layer of local history, often predating written records. When we change them, we erase a direct connection to the landscape and people of the past, however embarrassing that connection might seem.” This sentiment fuels modern campaigns. Whether it’s resisting the shortening of “Cockshoot” to “Coxhill” or proudly displaying souvenir mugs in Crapstone, communities now see these rude place names UK as badges of honour, unique selling points, and vital links to an authentic, unvarnished past.

The Tourism Titter: Postcards and Novelty Maps

Inevitably, commercial savvy has caught up with historical charm. What was once a source of local embarrassment or indifference is now a potent magnet for tourism and commerce. Villages like Wetwang in East Yorkshire or Twatt in Orkney have leaned into their notoriety, selling a vast array of memorabilia—postcards, mugs, t-shirts, and keyrings—to visitors who make a pilgrimage specifically for the photo opportunity by the village sign. This creates a curious, symbiotic relationship between place and visitor.

This “novelty tourism” brings economic benefits but also poses subtle questions about cultural respect. Is the location being celebrated for its genuine history and community, or merely consumed as a punchline? The most successful examples balance the two: they welcome the laughter and the spending, but also use the curiosity as a gateway to educate visitors about the real etymology and history behind the rude place names UK tourists flock to, transforming a snigger into a genuine learning moment.

Legal and Bureaucratic Challenges

Living with a notorious name isn’t all postcard sales and celebrity; it presents genuine everyday hurdles. One of the most common modern frustrations is with digital systems. Automated address checkers, online forms, and even some satnav databases often reject or auto-correct addresses containing words deemed “inappropriate.” Residents of Bell End or members of the Cocks family (a real surname concentrated in certain areas) frequently report issues with bank applications, delivery services, and government paperwork.

Furthermore, the very official bodies that govern place names, such as the Ordnance Survey and the Geographic Names Branch, now operate with modern sensibilities. While they are historically reluctant to change names without local consent, proposing a new rude place names UK development would be almost unthinkable. The process is fraught with considerations of offence, practicality, and legacy, highlighting the ongoing tension between preserving historical authenticity and navigating a connected, digital world with its own set of linguistic rules.

Beyond the Snigger: Names of Violence and Sorrow

While the scatological and sexual names draw the most attention, the UK’s map also harbours place names that speak of a darker, more violent past. These are not “rude” in the modern sense, but they are equally jarring and revealing. Names like Murder Moor in Devon, Slaughterbridge in Cornwall, or Breakheart Hill evoke tales of conflict, tragedy, or grim geography. The Doleful Ditch or Starvecrow Lane hint at hardship and hunger.

These names serve as solemn counterpoints to the more humorous ones. They remind us that place names were also records of memorable events, warnings, or acknowledgements of suffering. Exploring this facet broadens our understanding of the rude place names UK landscape; it wasn’t all bodily functions and innuendo. Sometimes, our ancestors used the landscape’s name as a stark memorial or a cautionary tale, etching their struggles and fears directly onto the geography for generations to remember.

A Comparative Glance: Is Britain Unique?

The natural question arises: is Britain uniquely blessed with this cartographic cheek? The answer is both yes and no. Countries with deep histories of settlement and linguistic layers, like Germany (with places like Kotzendorf – “Vomit Village”) or France (with Montcuq, pronounced similarly to a crude French phrase), have their own share of eyebrow-raising names. The United States, with its younger, often literal naming traditions, has its Dickshooter, Idaho, or Intercourse, Pennsylvania.

However, the UK’s particular combination is potent: an exceptionally long and well-documented history of settlement (Celtic, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Norse), followed by a concentrated period of Victorian repression, and finally a modern culture of nostalgic preservation and commercial exploitation. This trilogy of creation, suppression, and celebration creates a uniquely rich and self-aware tapestry. The density and variety of rude place names UK can offer, from ancient to accidental, arguably remain in a league of their own, a testament to a particularly unbuttoned chapter of linguistic history.

The Enduring Appeal: Why We’re Still Chuckling

The fascination with these names endures because it operates on multiple levels. On the surface, it’s pure, childish humour—the joy of the forbidden word, the thrill of seeing something “naughty” in an official context. It’s a universal icebreaker and a shared moment of levity. On a deeper level, it connects us to the humanity of our ancestors. It reminds us that they had humour, dealt with the same baser aspects of life, and communicated with a directness we’ve largely lost.

Ultimately, these names are a form of cultural time travel. They break down the formal, stiff image of history and reveal something more relatable and authentic. Every chuckle at a rude place names UK sign is, in its own way, a recognition of our shared human experience across the centuries. They prevent history from becoming too polished, too distant, and too serious, keeping it grounded in the wonderfully, messily real.

Conclusion

Our journey through the map of Britain’s most impolitely named locations reveals far more than a simple catalogue of juvenile jokes. These rude place names UK enthusiasts and historians cherish are, in fact, profound historical documents. They are linguistic palimpsests, showing the evolution of language from the practical to the provocative. They are records of social attitudes, from the blunt pragmatism of the Middle Ages to the repressive gentility of the Victorians, and finally to the proud, preservative spirit of modern communities.

They teach us that our landscape is not just shaped by geology and politics, but by humour, accident, and the everyday lives of ordinary people. From Shitterton’s giant stone to the souvenir shops of Wetwang, these names spark curiosity, drive tourism, and forge a unique local identity. They remind us that history is not monolithic; it is layered with laughter, sorrow, description, and occasional bewilderment. So, the next time you spot one of these glorious names on a map or a road sign, see past the immediate snigger. See it for what it truly is: an irreverent, indelible, and utterly human scratch on the surface of time.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the rudest place name in the UK?

This is subjective, but historically, the most explicitly rude was “Gropecunt Lane,” found in many medieval cities, though these have all been renamed. Among surviving rude place names UK, Shitterton in Dorset is a strong contender for its direct modern equivalence, though others like Crapstone or Twatt are equally famous for their phonetic impact. The “rudeness” is almost always a product of linguistic evolution, not original intent.

Why haven’t these rude names been changed?

Many were changed during the Victorian era. Those that remain have often survived due to strong local opposition to alteration. Communities now view these names as an important part of their unique heritage and history. There is often a concerted, passionate effort to preserve them, viewing any change as an erasure of the past and a surrender to unnecessary prudery.

Do people really live in these places?

Absolutely. These are not fictional entries on a novelty map but real, functioning villages, hamlets, and streets. Residents typically develop a robust sense of humour and local pride about their address. While they may face occasional bureaucratic hassles with automated systems, most would fiercely defend their rude place names UK against any official attempt to sanitise them.

Are these names unique to the UK?

While other countries have their own share of oddly or offensively named places, the UK’s combination is particularly rich due to its layered history of language (Old English, Old Norse), a well-documented period of Victorian name-changing, and a modern culture that celebrates this quirky heritage. The density and variety of such names across Britain is arguably unmatched.

What’s the best way to visit these places respectfully?

The key is to be a respectful visitor, not just a gawker. If you visit, do so with an interest in the genuine history and etymology, not just the joke. Support local businesses, read the village noticeboard, and perhaps even chat to residents (who are usually happy to share stories). Remember, you’re visiting someone’s home, which happens to have a famous, funny name. Appreciate the rude place names UK landscape as a fascinating historical phenomenon, not just a punchline.

You may also read

Dan Burn Wife: An Inside Look at the Newcastle Defender’s Private Life with Lucy Burn